the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

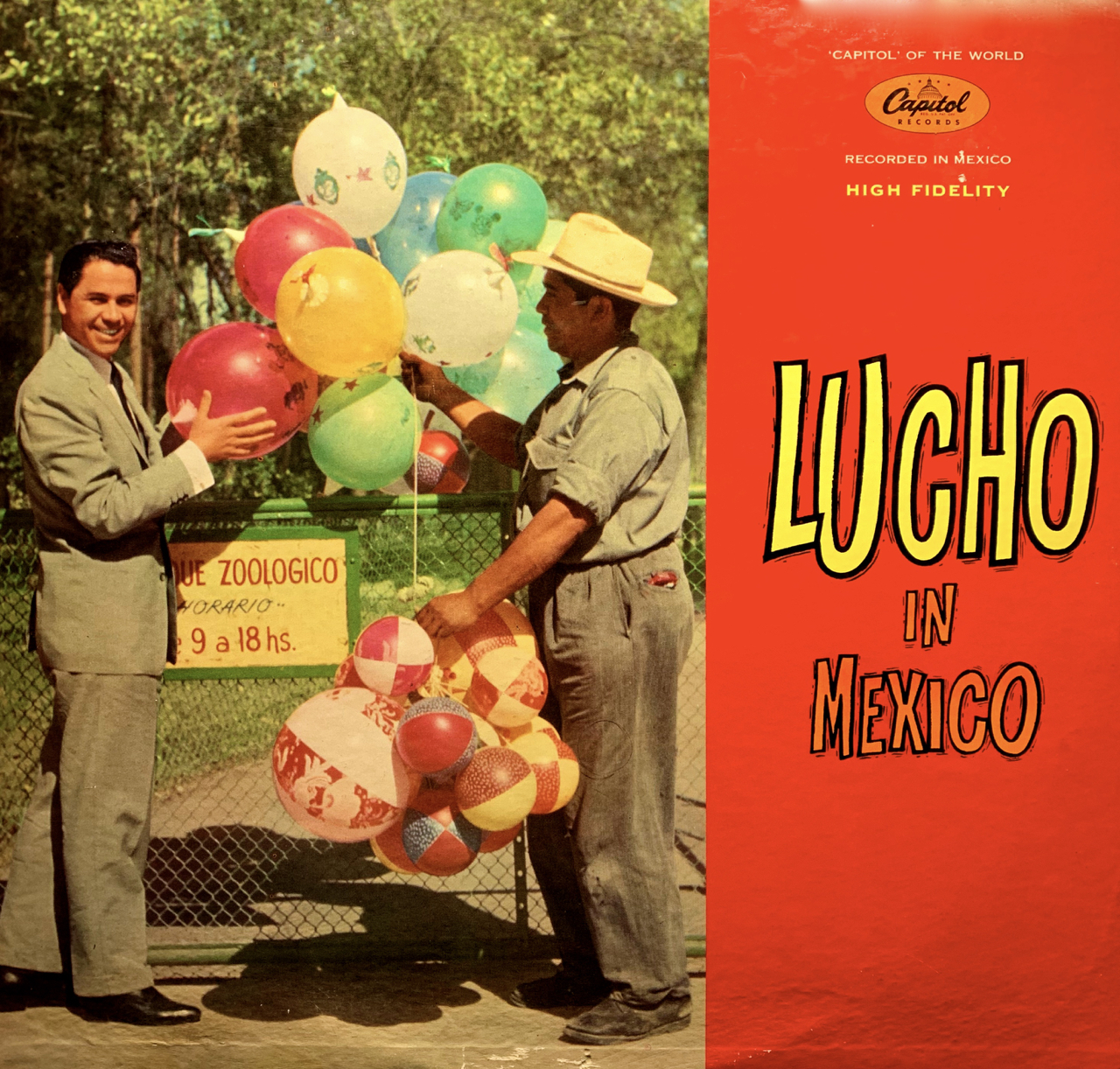

Mid-century Mexico was the hub of the Latin American entertainment industry, a leader in music and film production for the continent. But breaking into that establishment was not easy, especially for an outsider.

Mid-century Mexico was the hub of the Latin American entertainment industry, a leader in music and film production for the continent. But breaking into that establishment was not easy, especially for an outsider.

“Listen, México at that time was an extreme bunker of nationalism,” said Odeon Chile’s artistic director Rubén Nouzeilles, in an interview on a Chilean music website. “Nobody could go there to sing boleros because that was the patrimony of the Mexicans, just as nobody would think of donning a charro hat and go compete with (a mariachi star). Lucho Gatica, apart from being a great artist, was also a conquistador.”

And the conquest was swift. The singer quickly became part of bolero royalty in Mexico. He was soon turning out hit after hit, hosting his own TV show, and making a series of films with Mexico’s biggest stars.

During most of the 20th century, the world of Latin pop music was dominated by a handful of countries – Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, and of course, Spain. But in the 1950s, an exception to that rule became a sensation. His name was Lucho Gatica, and he came from Chile.

During most of the 20th century, the world of Latin pop music was dominated by a handful of countries – Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, and of course, Spain. But in the 1950s, an exception to that rule became a sensation. His name was Lucho Gatica, and he came from Chile.

Gatica emerged from a small town in central Chile to become one of the most popular Latin American vocalists of all time. In a career that spanned 70 years, he sold millions of records around the world, packed theaters and stadiums from Madrid to Manila, starred in movies, and became a celebrity in Hollywood where his friends included Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner.

The Frontera Collection is not a static library archive collecting digital dust. It is designed to be a dynamic, interactive cultural resource, open to contributions from researchers and music fans, as well as from friends and relatives of the thousands of artists represented in this incomparable record collection.

The Frontera Collection is not a static library archive collecting digital dust. It is designed to be a dynamic, interactive cultural resource, open to contributions from researchers and music fans, as well as from friends and relatives of the thousands of artists represented in this incomparable record collection.

Many Frontera followers have started offering feedback, comments, information, and appreciation. In some cases, their missives point us to hidden gems in the collection that otherwise may have gone unnoticed. Such was the case last month when a music fan from Caracas, Venezuela, contacted us about a song called “Ay Trigueña!” by Dúo Espin – Guanipa, a guitar-and-vocal duet on a Victor 78-rpm disc. I had never heard of the artists, nor this lovely old-fashioned song about a man’s yearning for the love of a beautiful woman with a wheat-colored complexion.

Every genre and sub-genre has its celebrated figures. Sometimes, they become internationally famous, like conjunto music legend Flaco Jimenez, or Afro-Cuban pianist Ruben Gonzalez of Buena Vista Social Club fame.

Every genre and sub-genre has its celebrated figures. Sometimes, they become internationally famous, like conjunto music legend Flaco Jimenez, or Afro-Cuban pianist Ruben Gonzalez of Buena Vista Social Club fame.

When Tejano music legend Jimmy Gonzalez died last month, the sad news did not make headlines around the world. But in Texas, fans mourned the loss of the beloved co-founder of Grupo Mazz, a towering band in modern Tejano music. His death on June 6 and the subsequent memorials made news on mainstream Texas television and in major English-language newspapers of cities such as Houston and San Antonio.

The pantheon of pioneers in conjunto music includes artists who are household names to fans and students of the genre. Among the most recognized are names such as Santiago Jimenez and especially Narciso Martinez, hailed as the father of the conjunto style. Although not as well-known as his celebrated contemporaries, accordion-player Pedro Ayala deserves recognition for his contributions to the early development of this grassroots style during the 1930s and 1940s.

The pantheon of pioneers in conjunto music includes artists who are household names to fans and students of the genre. Among the most recognized are names such as Santiago Jimenez and especially Narciso Martinez, hailed as the father of the conjunto style. Although not as well-known as his celebrated contemporaries, accordion-player Pedro Ayala deserves recognition for his contributions to the early development of this grassroots style during the 1930s and 1940s.

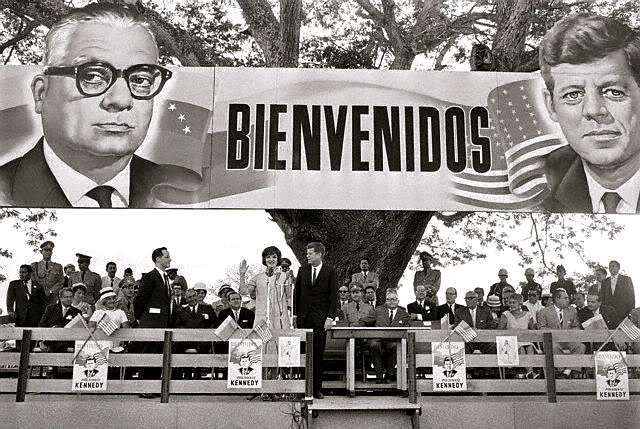

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. The slain presidential candidate was especially admired by the Mexican-American community, as was his martyred brother before him, President John F. Kennedy. That admiration was expressed poetically and emotionally in many songs written as tributes to the fallen leaders.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. The slain presidential candidate was especially admired by the Mexican-American community, as was his martyred brother before him, President John F. Kennedy. That admiration was expressed poetically and emotionally in many songs written as tributes to the fallen leaders.

In 1939, as the Depression was winding down and a new world war was heating up, Lalo Guerrero was still a struggling musician seeking to make his mark. He was newly married and dirt poor, with a son on the way and work hard to come by, keeping the young family on the move from gig to gig.

In 1939, as the Depression was winding down and a new world war was heating up, Lalo Guerrero was still a struggling musician seeking to make his mark. He was newly married and dirt poor, with a son on the way and work hard to come by, keeping the young family on the move from gig to gig.

In his autobiography, Lalo: My Life and Music, Guerrero called this period “our gypsy years.” Yet, the swing-music decade of the 1940s would also bring stardom and some stability to the young performer.

Lalo Guerrero, the son of immigrants from a poor barrio in Tucson, Arizona, was a pioneering musician whose bilingual songs and bicultural persona earned him the honorary title "The Father of Chicano Music."

Lalo Guerrero, the son of immigrants from a poor barrio in Tucson, Arizona, was a pioneering musician whose bilingual songs and bicultural persona earned him the honorary title "The Father of Chicano Music."

In a career that spanned seven decades, the versatile composer and performer wrote hundreds of songs in an astonishing array of styles, from romantic boleros to folkloric corridos, from comical parodies to rousing protest songs, from mambos to swing, rock, and cha cha chas. He had several international hit songs, appeared in movies alongside major Hollywood stars, operated a landmark nightclub in East L.A., and eventually earned the highest cultural honors awarded to entertainers.

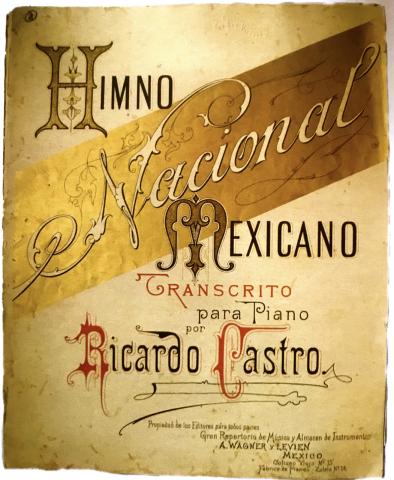

Every country has a story behind the creation of its national anthem. In my last blog, I recounted the complex history of the Mexican National Anthem, which originated under the reign of President Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Every country has a story behind the creation of its national anthem. In my last blog, I recounted the complex history of the Mexican National Anthem, which originated under the reign of President Antonio López de Santa Anna.

The Frontera Collection also contains recordings of anthems from nine other Latin American nations. Most of the Central and South American anthems were initiated in the years following the wars of independence from Spain, starting in 1810. As with Mexico, many of the new nations of the American continent struggled to find an appropriate national song, reflecting the tumultuous political struggles to establish new sovereign identities.

Americans remember Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna as the Mexican general who defeated Texas insurgents at the Alamo. Mexicans remember him as the self-aggrandizing leader who lost half the nation’s territory in the war with the United States. Few people, however, remember him as a patron of the arts. It’s a little-known fact that Santa Anna was the assiduous sponsor of a literary competition that produced the modern Mexican National Anthem, with lyrics by a reluctant poet and music by a classically trained Catalan composer.

Americans remember Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna as the Mexican general who defeated Texas insurgents at the Alamo. Mexicans remember him as the self-aggrandizing leader who lost half the nation’s territory in the war with the United States. Few people, however, remember him as a patron of the arts. It’s a little-known fact that Santa Anna was the assiduous sponsor of a literary competition that produced the modern Mexican National Anthem, with lyrics by a reluctant poet and music by a classically trained Catalan composer.

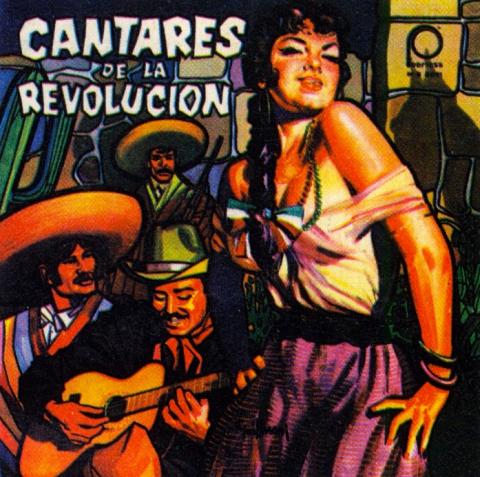

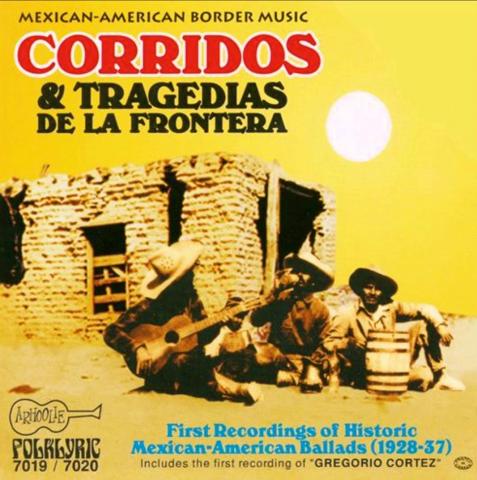

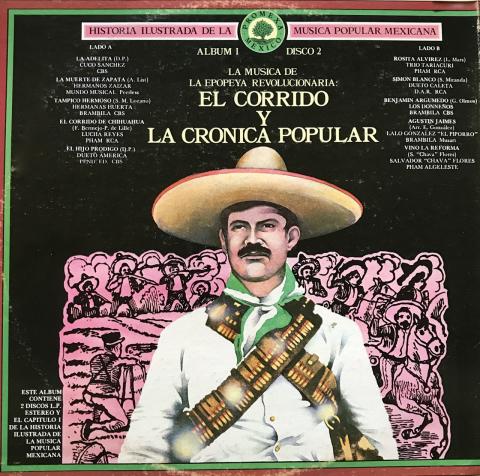

The Mexican Revolution of 1910, with its epic heroes facing life-and death struggles, ushered in a golden age of the corrido. In the introduction to his 1954 anthology, “El Corrido Mexicano,” corrido historian Vicente T. Mendoza asserts that the narrative ballad achieved its “definitive character” during Mexico’s decade of Civil War, acquiring “its true independence, fullness and epic character in the heat of combat.”

The Mexican Revolution of 1910, with its epic heroes facing life-and death struggles, ushered in a golden age of the corrido. In the introduction to his 1954 anthology, “El Corrido Mexicano,” corrido historian Vicente T. Mendoza asserts that the narrative ballad achieved its “definitive character” during Mexico’s decade of Civil War, acquiring “its true independence, fullness and epic character in the heat of combat.”

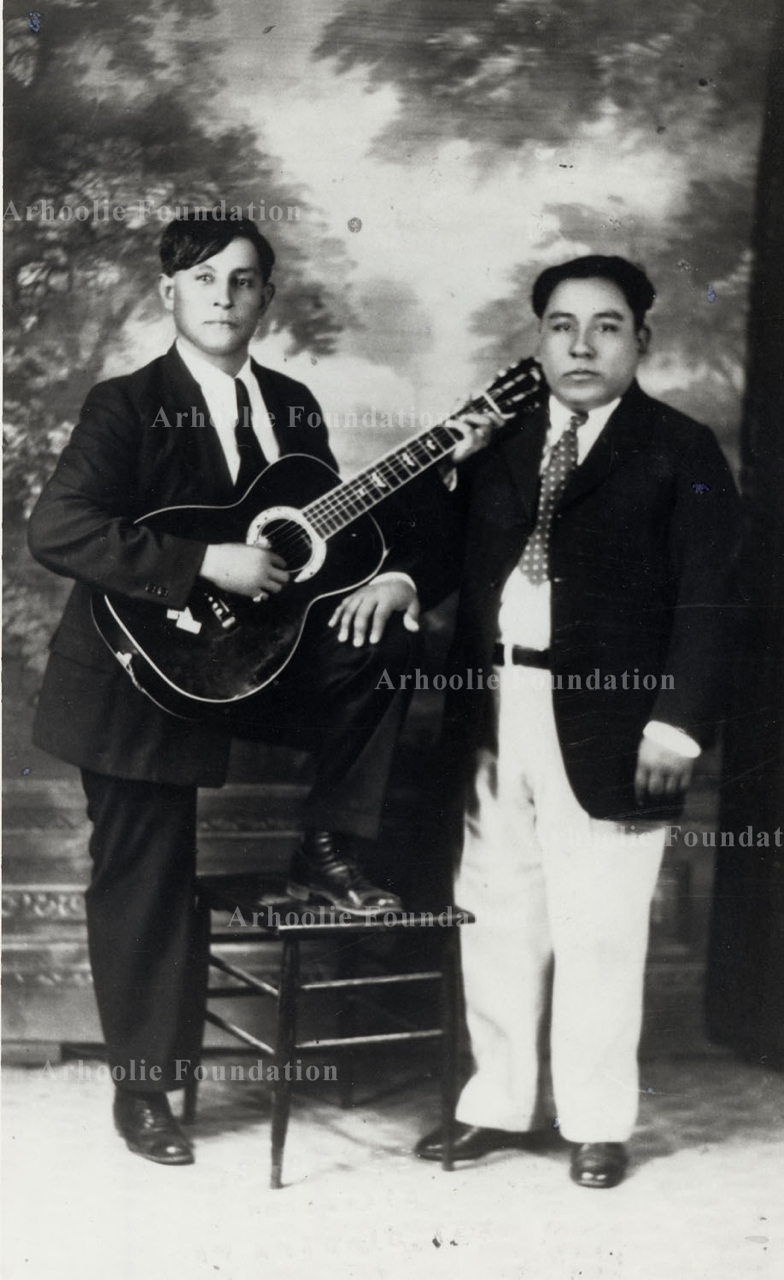

During the first half of the 20th century, the corrido went from an oral tradition to a recorded, commercial art form. But in making that transition, corrido artists had to adapt their long narrative ballads to the recording technology of the day, primarily the old 78-rpm shellac discs.

During the first half of the 20th century, the corrido went from an oral tradition to a recorded, commercial art form. But in making that transition, corrido artists had to adapt their long narrative ballads to the recording technology of the day, primarily the old 78-rpm shellac discs.

As we saw in Part 1, the corrido developed as an oral tradition in the last half of the 19th century. The narrative ballad was cultivated along the border, fueled by the cultural conflict left in the wake of the U.S. War with Mexico. These early border ballads, which reached their peak between 1860 and 1910, depicted the exploits of protagonists caught up in these culture wars, often through no desire of their own.

As we saw in Part 1, the corrido developed as an oral tradition in the last half of the 19th century. The narrative ballad was cultivated along the border, fueled by the cultural conflict left in the wake of the U.S. War with Mexico. These early border ballads, which reached their peak between 1860 and 1910, depicted the exploits of protagonists caught up in these culture wars, often through no desire of their own.

The corrido is often described as a narrative ballad, which is an accurate though insufficient definition. Narrative ballads exist in many countries, including the United States. But the form that developed in Mexico in the late 1800s is deeply rooted in that country’s specific cultural history, and especially the inequitable relationship with its conquering neighbor to the North.

The corrido is often described as a narrative ballad, which is an accurate though insufficient definition. Narrative ballads exist in many countries, including the United States. But the form that developed in Mexico in the late 1800s is deeply rooted in that country’s specific cultural history, and especially the inequitable relationship with its conquering neighbor to the North.

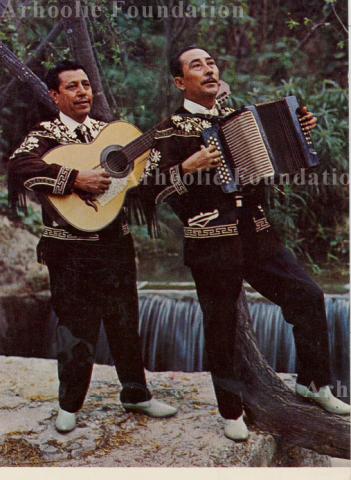

Los Alegres de Terán, a vocal duet founded by a pair of humble migrant workers from northern Mexico, stands as one of the most influential, long-lived and commercially successful regional music acts from the last half of the 20th century. The duo of Tomás Ortiz and Eugenio Ábrego are today remembered as the fathers of modern norteño music, the accordion-based country style that traversed borders as fluidly as its immigrant fans.

Los Alegres de Terán, a vocal duet founded by a pair of humble migrant workers from northern Mexico, stands as one of the most influential, long-lived and commercially successful regional music acts from the last half of the 20th century. The duo of Tomás Ortiz and Eugenio Ábrego are today remembered as the fathers of modern norteño music, the accordion-based country style that traversed borders as fluidly as its immigrant fans.

When we consider where Latinos live in the U.S., we don’t usually think of states in the Deep South. We think of California, Texas, and New York; not Mississippi, Georgia, or Alabama. Census reports, as of 2012, show that the states with the highest percentage of Latino residents are all in the West and Southwest, followed by Florida, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois to round out the Top 10. But if you rank states where the Latino population is growing the fastest, 8 of the top 10 spots are taken by Southern states. And each of those states has at least doubled its Latino demographic between 2000 and 2010.

When we consider where Latinos live in the U.S., we don’t usually think of states in the Deep South. We think of California, Texas, and New York; not Mississippi, Georgia, or Alabama. Census reports, as of 2012, show that the states with the highest percentage of Latino residents are all in the West and Southwest, followed by Florida, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois to round out the Top 10. But if you rank states where the Latino population is growing the fastest, 8 of the top 10 spots are taken by Southern states. And each of those states has at least doubled its Latino demographic between 2000 and 2010.

The corrido is a traditional Mexican ballad that tells true stories of heroes and villains in verse. It was once considered a reliable news source, in the era when the poor had limited access to other forms of media. Today, corridos are still written about current events, from the terrorist attacks of 9/11 to the battles over immigration and the election of Donald Trump.

The corrido is a traditional Mexican ballad that tells true stories of heroes and villains in verse. It was once considered a reliable news source, in the era when the poor had limited access to other forms of media. Today, corridos are still written about current events, from the terrorist attacks of 9/11 to the battles over immigration and the election of Donald Trump.

Mexican-Americans have always felt a patriotic pride in performing military service to their adopted homeland. But they’ve had to fight on another front, too: getting due credit for doing their duty. Ten years ago, filmmaker Ken Burns came under fire for ignoring the contributions of Latino soldiers in his World War II documentary, The War. After activists intensely lobbied PBS, which aired the documentary, the filmmaker begrudgingly amended his film to represent the 300,000 Latinos who fought in that war.

Stay informed on our latest news!