El eterno bolero, parte 3: Sigue vivo

Puede que el bolero ya no sea lo que era, pero como dicen en el mundo del espectáculo, tuvo una gran carrera. Además, ha tenido algún que otro renacimiento.

Como la mayoría de los estilos musicales populares, el bolero tuvo su apogeo antes de desvanecerse de la corriente comercial. Disfrutó de un período de éxito sostenido que abarcó un tercio del siglo XX, desde los años treinta hasta los sesenta. Sin embargo, su popularidad disminuyó a raíz de las nuevas corrientes musicales.

El bolero sufrió un notable bajón en los años 80, una década de grandes cambios en la música latina. El rock en español estaba en auge en España y América Latina. La música tradicional mexicana, que a menudo incluía boleros rancheros, empezaba a perder terreno frente al controvertido narcocorrido y el estilo de banda ruidoso y estridente de la costa del Pacífico mexicano. Mientras tanto, en la costa atlántica de los Estados Unidos, los sonidos picantes del reggaetón de Puerto Rico y Panamá atraían a una nueva generación con letras profanas y bailes indecentes que dejaban poco espacio para la ternura poética y el romanticismo anticuado de las canciones de amor tradicionales y gentiles.

A medida que se acercaba el final del milenio, el bolero lírico parecía cosa del pasado.

Sin embargo, el bolero no es una moda pasajera, como la música disco o La Macarena, ni un estilo anclado en la historia, como el ragtime o la contredanse francesa. Es un estilo de canción muy vivo y en evolución, refrescado por nuevos compositores y jóvenes generaciones de aficionados.

Como estilo de canción, el bolero es más comparable a la música del cancionero americano clásico, con canciones estrechamente vinculadas a compositores verdaderamente icónicos como Cole Porter, Irving Berlin y equipos de compositores estelares como George e Ira Gershwin y Rodgers y Hammerstein. Por mucho que los crooners famosos interpretaran sus melodías (Sinatra, Bennett, Fitzgerald), las canciones siempre llevaban la marca de los compositores.

Del mismo modo, los boleros están menos vinculados a sus distintos intérpretes que a sus afamados compositores, considerados piedras angulares de la cultura latinoamericana, no solo creadores de un estilo de canción. Decir los nombres de Agustín Lara o César Portillo de la Luz es evocar una época, una visión del mundo, una forma de vida. Estos queridos cantautores y su música nunca caerán en desgracia, ni desaparecerán de la memoria colectiva.

La longevidad del género se confirmó con el renacimiento del bolero que surgió inesperadamente durante la década de 1990. Este renacimiento se vio impulsado por dos tendencias nostálgicas independientes que abrieron y cerraron la década como si fueran sujetas. Estos dos resurgimientos se produjeron en los dos países que habían servido de fuentes gemelas del género: México y Cuba.

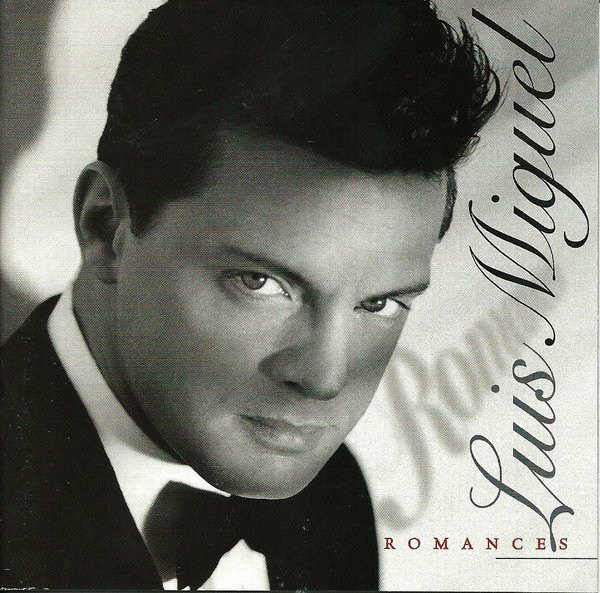

En 1991, como ya he mencionado, Luis Miguel desató la moda del bolero en México con el primer álbum de su trilogía Romances, una serie de grabaciones que ofrecían su visión moderna de canciones clásicas del género, adornadas con nuevos arreglos orquestales. En su conjunto, la serie del cantante sirvió para hacer un repaso de las canciones de amor más duraderas del mundo hispanohablante. (Casualmente, sus grabaciones incluyen muchas de las canciones que destaqué como mis preferidas en Parte 1 y Parte 2. Tal vez sea de esperar; los aficionados al bolero comparten la afinidad por las mismas melodías queridas del repertorio).

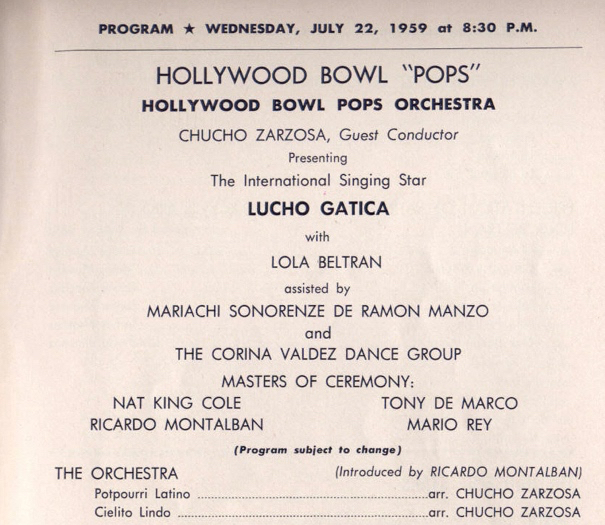

Seis años más tarde, en 1997, el guitarrista estadounidense Ry Cooder visitó Cuba y ayudó a lanzar Buena Vista Social Club, el conjunto de artistas de la vieja guardia de renombre internacional, que incitó una locura propia de nostalgia por la música tradicional cubana en todo el mundo. Los discos de Buena Vista y sus estrellas solistas – Omara Portuondo, Ibrahim Ferrer, Compay Segundo – no se concentraron en los boleros. Pero como se centraban en la música de la época dorada del género en Cuba, las grabaciones incluían varios boleros salpicados, presentando al público no latino estas viejas canciones clásicas por primera vez.

En esta última entrega de mi serie de blogs sobre el bolero, presento boleros que resurgieron durante el renacimiento de la década de los 90. Estas canciones podrían haber figurado fácilmente en las dos primeras entregas, ya que también son canciones que aprendí durante mi infancia y juventud. Pero los blogs tienen límites, mientras que la lista de buenos boleros parece interminable.

Sin embargo, sería negligente terminar una revisión extensa del género sin mencionar a Armando Manzanero, uno de los mejores compositores mexicanos de la última mitad del siglo XX. Con sus cautivadoras composiciones de las décadas de 1970 y 1980, el yucateco tendió un puente entre la época del bolero histórico y el renacimiento de finales de siglo. No es casualidad que acabara coproduciendo los exitosos LPs de renovación de Luis Miguel.

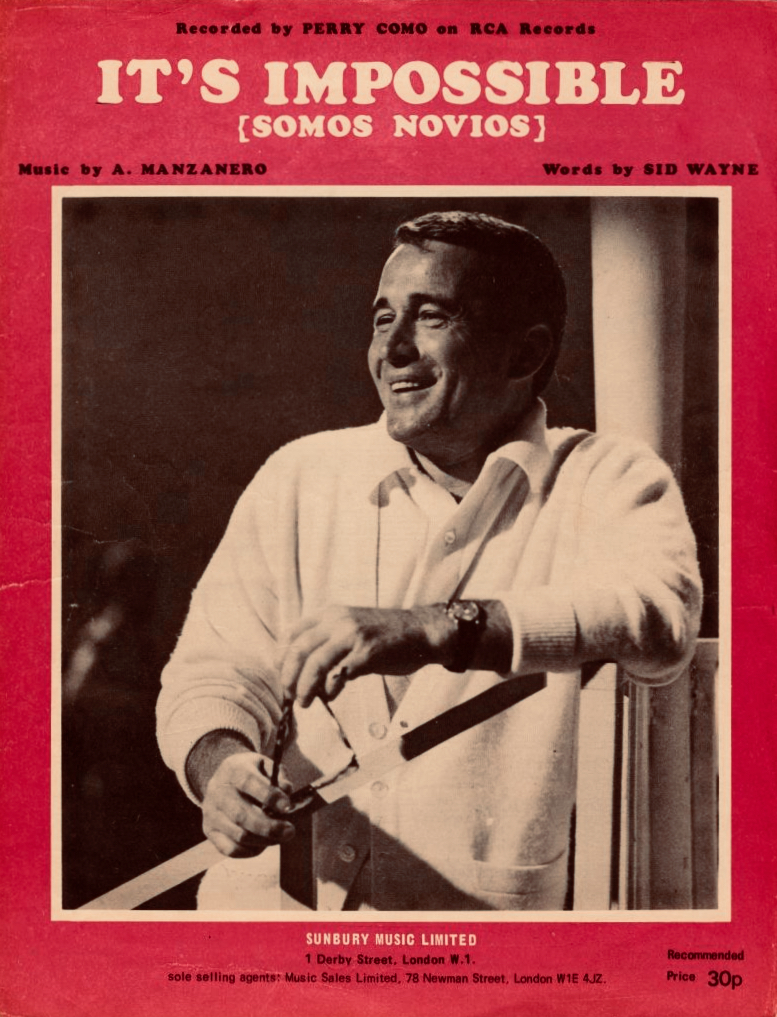

En nuestra boda de 2002, mi mujer y yo tocamos uno de los mayores éxitos de Manzanero, "Somos Novios", que Manzanero había compuesto y grabado en 1968. El propio compositor toca el piano en este concierto de Luis Miguel.

La mayoría de los aficionados estadounidenses reconocerán la canción en su traducción al inglés, "It's Impossible", con una nueva letra escrita en 1970 por Sid Wayne. Ese mismo año, la melodía traducida fue grabada por primera vez por Perry Como, quien la convirtió en su primer éxito en el Top 10 en más de 12 años.

"It's Impossible" sigue siendo una de las canciones en español más versionadas de todos los tiempos, con versiones de artistas tan variados como Johnny Mathis (1971), Elvis Presley (1973), Vic Damone (1997), Julio Iglesias (2006), Andrea Bocelli (2006) y Engelbert Humperdinck a dúo con Manzanero (2014), por no hablar de casi cuatro docenas de interpretaciones instrumentales de artistas como Mantovani (1971), Los Indios Tabajaras (1971) y The Ventures (1979).

A lo largo de su carrera, Manzanero escribió más de 400 canciones, entre las que destacan los éxitos "Esta Tarde Vi Llover", "Contigo Aprendí" y "Adoro", que también figuran entre mis preferidas.

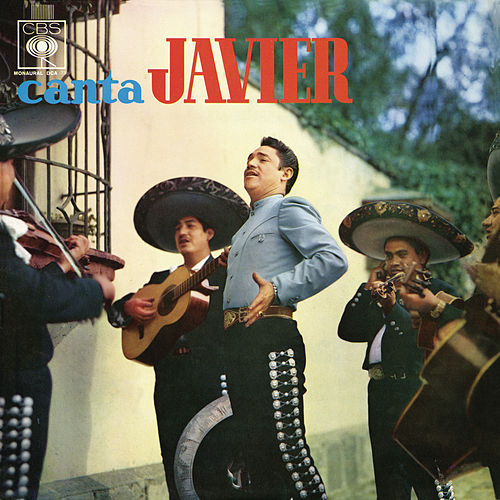

El célebre cantautor falleció el 28 de diciembre de 2020 a los 83 años. Casi un año después, el 12 de diciembre de 2021, México perdió a otra gran figura musical, Vicente Fernández, que definió de forma indeleble la música ranchera en la última mitad del siglo XX. Apodado "El Rey" y "El Ídolo de México", Fernández fue un maestro del bolero ranchero, con una voz que podía fluctuar entre la potencia operística y la vulnerabilidad susurrada.

Los obituarios en inglés suelen mencionar los éxitos característicos de Fernández, como "El Rey" y "Volver, Volver". Pero grabó muchos boleros memorables que captaban las profundidades agónicas del anhelo y la pérdida, así como las tiernas pasiones, intrínsecas al género. Como aficionado desde hace 50 años, algunos de mis boleros favoritos de Chente son "Acá Entre Nos", "A Pesar de Todo", "Por Tu Maldito Amor", "Que de Raro Tiene", "Mujeres Divinas", "De Qué Manera Te Olvido", "Hermoso Cariño" y muchísimos más.

A estas alturas de mi vida de melómano empedernido, no hay muchos boleros famosos que no conozca. Sin embargo, el Nostalgic Nineties me ha recordado unos cuantos que me encantan y que son dignos de mención en esta última entrega. Siguiendo con el concepto de recapitulación, he creado también una lista de reproducción en Spotify con mi lista de los 40 mejores boleros, incluyendo los que he presentado en esta serie y algunas joyas más de mi biblioteca de canciones de amor más queridas.

“Bésame Mucho” por Consuelo Velasquez & Daniel Riolobos

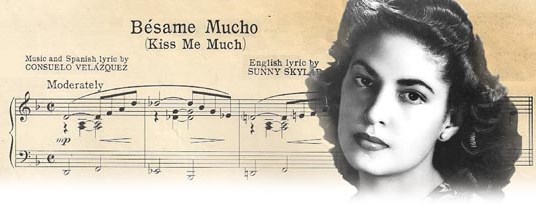

El reportero Morley Safer, de 60 Minutes, dijo una vez en el aire que esta era la peor canción jamás escrita. Supongo que ninguna mujer ha deseado tanto sus besos, que es mucho. Tal vez Safer se perdió el significado, y el sentimiento, en la traducción. "Kiss Me a Lot" ("Bésame muchas veces") no sirve, porque lo importante no es el número de besos, sino la pasión sostenida e intensa de besos que se funden en uno solo. La canción es un clásico, escrita por una de las pocas mujeres en el panteón de los compositores de boleros, la mexicana Consuelo Velázquez. Consigue mezclar en sus letras el deseo apasionado y el temor a la separación.

Tras su muerte, en 2005, a los 88 años, The New York Times destacó su canción más famosa. "Bésame Mucho" no es tanto un estándar perdurable como un fenómeno global", decía el obituario. "Traducida a docenas de idiomas e interpretada por cientos de artistas, la canción ha sido un emblema de la identidad latina, un himno de los amantes separados por la Segunda Guerra Mundial y una fuente perenne para los cantantes de salón del mundo entero".

Velázquez también compuso la seductora melodía de la canción, que realza eficazmente la emoción, como demuestran las numerosas versiones instrumentales de la melodía, incluida esta versión jazzística de Dave Brubeck. Es una de las canciones más versionadas de la música latina, con versiones de Josephine Baker, Charro, los Coasters, Nat King Cole, Xavier Cugat, Plácido Domingo, Bill Evans, Connie Francis, Harry James, Diana Krall, Trini Lopez, Dean Martin, Art Pepper, los Platters, Tito Puente y (famosamente) los Beatles. En la insólita actuación enlazada arriba, el compositor toca el piano para acompañar al cantante argentino Daniel Riolobos, que entra en el escenario y, sorprendentemente, empieza a cantar la canción por la mitad, con el puente que presagia la separación de la pareja.

Quiero tenerte muy cerca,

Mirarme en tus ojos,

Verte junto a mí.

Piensa que tal vez mañana

Yo ya estaré lejos,

Muy lejos de aquí

“Historia de Un Amor” por Luis Miguel

El joven cantante hace maravillas con este bolero de desamor y pérdida, que tanto se ha grabado. Es uno de esos estándares que se dan por hecho, con letras que pueden aplicarse a cualquier relación que sufra una separación. Sin embargo, la mayoría de los aficionados desconocen el desamor real que hay detrás de la canción.

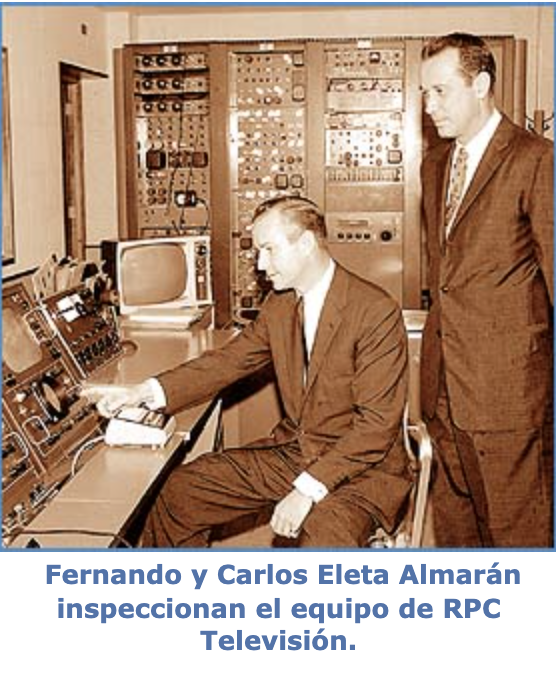

Fue escrita en 1955 por Carlos Eleta Almarán, tal vez el único cantautor panameño que llegó a la cima de los boleristas con esta melodía. La escribió como una dolorosa despedida tras la prematura muerte de su cuñada, Mercedes, esposa de su hermano Fernando. Ella murió de poliomielitis en 1954, tras solo cuatro años de matrimonio, dejando atrás a tres hijos.

Las letras de Almarán adquieren un significado más profundo a la luz de las trágicas circunstancias de sus orígenes. La permanencia de la pérdida es subrayada por la melodía que llega a un crescendo, y luego a un desenlace, cuando las palabras lamentan que la luz del amor se haya extinguido para siempre por una ausencia eterna.

Es la historia de un amor,

como no hay otro igual.

Que me hizo comprender

todo el bien, todo el mal.

Que le dio luz a mi vida,

apagándola después.

Ay, qué vida tan oscura

Sin tu amor no viviré.

Almarán (en los créditos de sus canciones, se utiliza su apellido materno en lugar de Eleta, el apellido de su padre) fue también un empresario de éxito. En 1960, fundó, junto con su hermano, la primera y ahora más antigua cadena de televisión de Panamá, RPC TV. Fernando, con títulos de Stanford y el MIT, se volvió a casar y ocupó altos cargos en el gobierno.

Mientras tanto, la canción que los unió en el trauma alcanzó el éxito mundial. Fue grabada por primera vez en 1955 por Libertatd Lamarque, y apareció en la película mexicana del mismo nombre. Al año siguiente, el argentino Héctor Varela, compañero de Lamarque, y su orquesta típica la transformaron en un tango.

A lo largo de los 66 años que han transcurrido, la canción ha sido versionada por una constelación de estrellas: Guadalupe Pineda, Marco Antonio Solís, David Bisbal, Lola Flores, Marco Antonio Muñiz, Pedro Infante, Ana Gabriel, Eydie Gormé & Trio Los Panchos, Julio Iglesias, Pérez Prado, Pedro Infante, Cesaria Evora, Eartha Kitt, Il Divo y Diego El Cigala.

Además, ha sido traducida a varios idiomas, entre ellos el chino, el inglés, el húngaro, el rumano, el finlandés y el francés.

La Mentira (Se Te Olvida) por Luis Miguel

Este bolero, "La Mentira", fue escrito por Álvaro Carrillo (1921-1969), uno de los compositores más prolíficos de México. El compositor ha escrito más de 300 canciones, incluyendo la que quizá sea el bolero más popular de todos los tiempos, "Sabor a Mí", que presenté en mi entrada "Romance y Revolución en 'Sabor a Mí'".

“Veinte Años” por Buena Vista Social Club

Esta triste canción entró en el canon de los boleros cubanos casi desde el momento de su estreno en 1935, con su triste letra de Guillermina Aramburu y la melancólica melodía de la compositora María Teresa Vera (1895-1965). Sin embargo, la canción se atribuye casi siempre exclusivamente a Vera, por razones que la mayoría de la gente, incluido yo mismo, desconocía hasta hace poco. Al parecer, Aramburu escribió los versos tras el fracaso de su matrimonio de 20 años, de ahí el título. Según el sitio web musical madrileño Radio Gladys Palmera, la letrista le dio la letra a Vera, su amiga desde la infancia, con la condición de que no revelara quién la había escrito.

Clasificada técnicamente como habanera, la canción se interpretaba originalmente con un sencillo acompañamiento de guitarra, al estilo de la trova tradicional cubana. Vera hizo una primera grabación de la melodía con su compañero de entonces, Lorenzo Hierrezuelo, un dúo formado a mediados de la década de 1930, más o menos al mismo tiempo que se escribió la canción. Su colaboración duró un cuarto de siglo. Durante ese tiempo, Hierrezuelo también formó la mitad de otro famoso dúo, Los Compadres; en este último cantaba la voz principal y se le apodaba Compay Primo, mientras que su compañero, Francisco Repilado, se encargaba de las armonías, o segunda voz, y por ello se le conocía como Compay Segundo, quien surgió décadas después como miembro destacado del Buena Vista Social Club.

"Veinte Años" aparece en decenas de grabaciones, especialmente de Cuba. Tengo casi tres docenas de versiones en mi colección privada. Entre mis preferidas está la excepcional interpretación de Bebo & Cigala, el dúo hispano-cubano compuesto por Bebo Valdés y el cantaor Diego El Cigala. Otra versión, más tradicional, fue grabada en 1964 por la cantante cubana Celeste Mendoza. Está respaldada por el popular grupo de renacimiento del son de La Habana, Sierra Maestra, dirigido por Juan de Marcos González, una fuerza creativa clave en la creación del grupo Buena Vista que amplió y mejoró su misión de preservar la música tradicional del son de la Sierra Maestra.

Y la historia cierra el círculo.

La canción tenía 60 años cuando se grabó para el álbum inaugural de Buena Vista (1997), y más tarde se incluyó en el álbum auto titulado en solitario (2000) de la querida cantante del conjunto, Omara Portuondo.

Pero nada iguala el encanto desgarrador de una versión reciente de un dúo de hermanos conocido como Isaac et Nora, una pareja de jóvenes surcoreanos que viven en Bretaña, en el noroeste de Francia. En su clip informal de YouTube de 2019, los niños cantan tímidamente las letras en español, mientras Isaac toca un solo de trompeta y su padre con lentes toca la guitarra en el fondo, mostrando ocasionalmente sonrisas de aprobación.

En un asombroso desarrollo que nunca podría haberse previsto por la generación bolerista, este vídeo de "Veinte Años" ha acumulado más de 7 millones de visitas. El dúo de hermanos se ha disparado en popularidad mundial. Tienen un nuevo álbum de estándares latinos, Latin & Love Studies, una página de Facebook pulida y profesional con 1,4 millones de seguidores, y un canal de YouTube que ha atraído casi 57 millones de visitas.

Y el bolero sigue vivo.

– Agustín Gurza

Also in this series:

The Eternal Bolero, Part 1: Love Songs That Endure for Decades

The Eternal Bolero, Part 2: Songs I Learned in College

Blog Category

Tags

Images